ML goes to Hell: Sentiment analysis supports the Marx's Inferno hypothesis

marxs_inferno.RmdAt the entrance to science, as at the entrance to hell, the demand must be made: “Here you must abandon every suspicion; here must all your cowardice die.”

- 1859 Preface, Marx, quoting Dante’s Divine Comedy

Capital is dead labour, that, vampire-like, only lives by sucking living labour, and lives the more, the more labour it sucks.

- Capital Vol 1, Marx 1867

Introduction

In Capital, Marx famously uses vivid metaphors, like monsters and vampires, to describe the uniquely exploitative nature of capital. But, what if the entire organization of the book was itself an infernal metaphor?

William Clare Roberts wrote a book, Marxs Inferno (2017), that argues that Marx structured his argument in Capital along the literary framework of Dante’s Inferno — yes, the 14th century poem about a guy traveling through Hell. (Marx’s Inferno argues a few other things, like that Capital should be read as an answer to contemporary socialist debates, but this part about the Divine Comedy is its “weirdest and most ambitious claim” and the one I’ll focus on here.)

In Inferno, Dante is guided by the ancient poet Virgil through the nine circles of Hell. At the center of Hell, they encounter Satan devouring Judas and other famous betrayers. They escape Hell by climbing down Satan’s legs, and pass through the center of the universe. In Roberts’ reading of Capital, “Marx (…) cast himself as a Virgil for the proletariat, guiding his readers through the lower recesses of the capitalist economic order in order that they might learn not only how this ‘infernal machine’ works, but also what traps to avoid in their efforts to construct a new world.”

Just as comparing capital to a vampire draining the life force of labourers communicates capital’s unbounded parasitism, building Capital as an allusion to Dante’s Inferno helps communicate a few complex ideas. Marx’s opponents were divided between those preoccupied with the moralistic questions of socialism who wished to avoid political economy and those who wished to stay firmly within classical political economy. In this literary allusion, we encounter moral failures (incontinence, violence, fraud, treachery), but Marx rejects this moralistic framework. Rather than the exploitation of labourers occurring by the greed and malevolence of individual capitalists, it is capital itself that inherently, impersonally, leads to exploitation. Secondly, by comparing the proletariat with Dante, Marx “emphasizes the necessity of going through political economy in order to get beyond it”, of confronting Satan/capital in order to escape their Hell (Roberts, 2017).

Roberts supports his reading of Capital by presenting how fond of Dante Marx was, how often Marx structured his other writings around literary works, and how clues from the drafting process suggest an intent to make his book more like Inferno. But is there support for this theory, of a descent through Hell, in the choice of language used?

Sentiment analysis is a type of natural language processing (NLP) method that attempts to understand the emotions and other subjective information in text. This kind of analysis is used, for example, by social media sites to flag offensive content. If Capital is patterned as a descent through Hell, we might expect the sentiment of the text to become increasingly negative. Let’s test that hypothesis!

Methods

I removed stop words from the main text of Capital (e.g., “the”, “a”, and other linker words) using the onix and snowball lexicons available through tidytext. I tokenized the text into individual words, extracted the word stem (i.e., made it so that words like “worship” and “worships” were treated identically) and then ascribed one or more sentiments to a word-stem using the NRC lexicon. This lexicon was developed through crowd-sourcing relationships between words and emotions (via Amazon’s Mechanical Turk), and has been widely used (>1800 citations on Google Scholar). I selected this lexicon because, of the four lexicons available in the tidytext package, the NRC lexicon mapped to the highest proportion of words. However, the same analysis conducted with the Bing, AFINN and Loughran lexicons recapitulated the trends shown here.

For the positivity/negativity analysis, positive words were assigned a value of 1 and negative words were assigned a value of -1. Net sentiments were calculated and normalized to the total number of words matched with a sentiment. I excluded words from consideration if they were considered both positive and negative, or if no sentiment could be ascribed. For the assessment of other sentiments, the sum of words across each sentiment was normalized to the word count in each hell, and then normalized to the sentiment value of the first circle of Hell (for clearer data visualization). I excluded the word “money” from this analysis since it occurs with very high frequency; with “money” included in the analysis, sentiments associated with money (i.e., the emotions anger, anticipation, joy, surprise and trust) reflected primarily the incidence of the word “money.”

The Circles of Hell In Capital

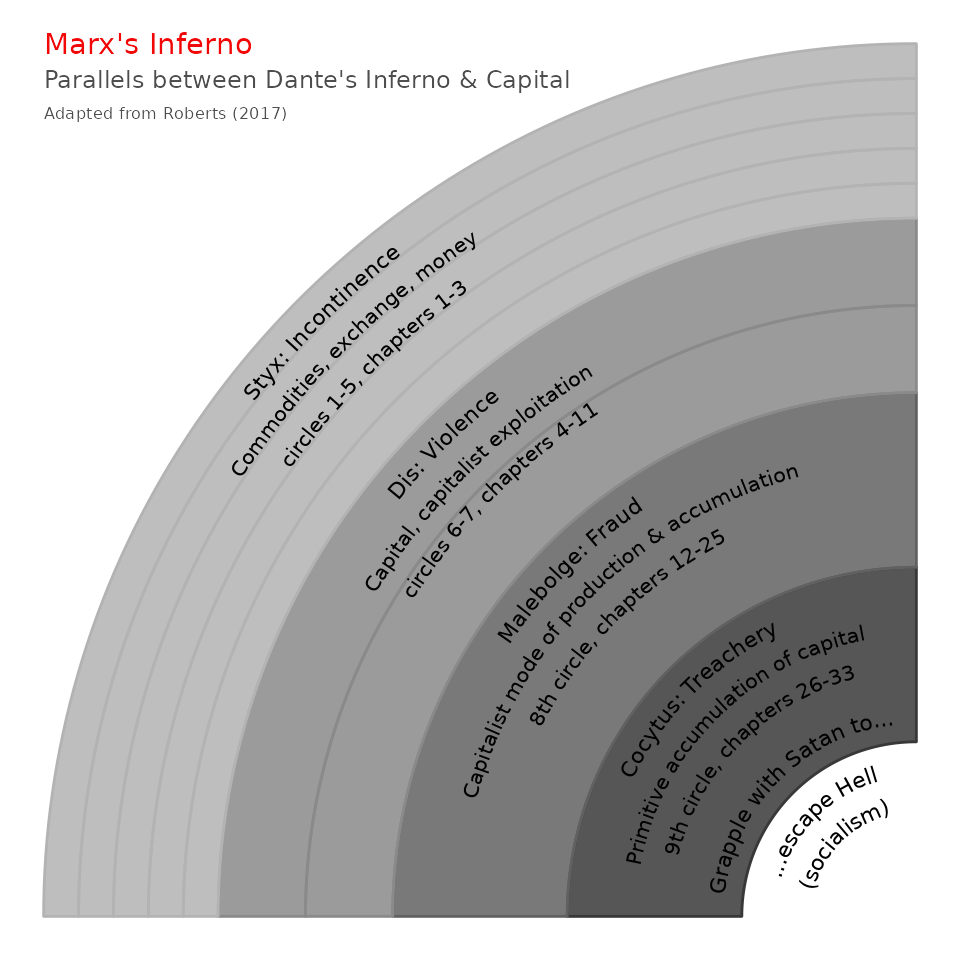

Figure 1: Similarities between Dante’s Inferno and Capital. (Admittedly I just wanted an excuse to use geomtextpath)

Before we get into the results, let’s quickly recap Roberts’ argument for the similarities between Capital and Inferno. Roberts breaks both texts into four sections, as summarized in the figure above.

-

Styx (circles 1-5, chapters 1-3): Sins of incontinence; commodity fetishism.

The impersonal domination of market-based societies allows for free movement of capital and products rather than control of capital/products by its producers. -

Dis (circles 6-7, chapters 4-11): Sins of violence; capitalist exploitation.

The relationship between capitalists and their workers is inherently one of force, as the boss controls and uses the workers to extract as much surplus value as possible from the labour power sold by the labourer. -

Malebolge (8th circle of Hell, chapters 12-25): Sins of fraud; the capitalist mode of production.

While capitalism may promise improved productivity in the form of mechanization, co-operation, division of labour and other efficiencies of scale, it delivers little of these gains to the workers but instead produces alienation and miserable working conditions. -

Cocytus (9th circle of Hell, chapters 26-33): Sins of treachery; primitive accumulation.

Betrayals presented here include: (a) the expropriation of land from the peasants in violation of the mutual obligation between serfs and their lords,

- the betrayal of the aristocrats in their new-found wealth by capital as the capitalists/bourgeoisie are freed by the abolition of feudalism, (c) the treachery of the state, acting as the agent of capital to do its “dirty” work, and (d) that workers attempting to wield capitalism for their own benefit will inevitably find themselves betrayed by the nature of capital.

It is only by moving past capitalism, by challenging Satan, that labourers can free themselves from oppression:

If Dante must confront Satan in order to escape his realm, then so must the labouring classes confront capital in order to escape the social Hell. Instead of trying to create their own capital, the labourers must realize that capital is a wealth that betrays and turns against its creators. (Roberts, 2017)

Positive and Negative Sentiments in Capital

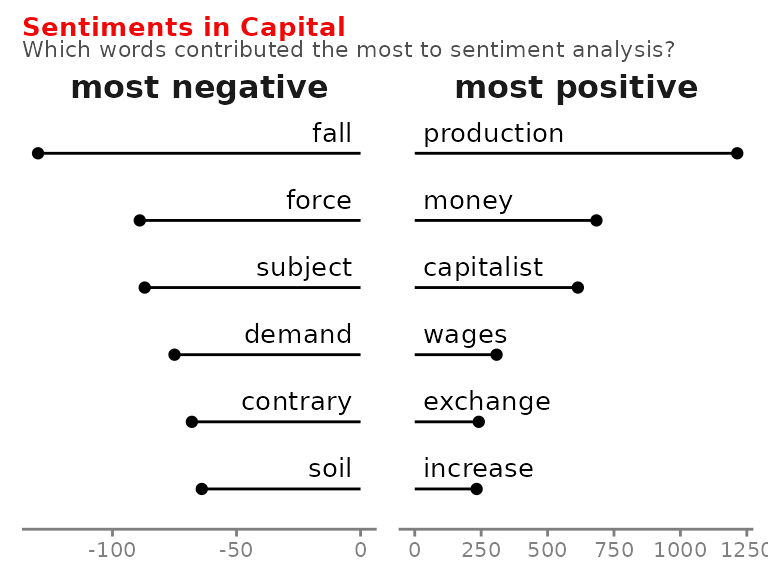

Marx explains the positive and negative aspects of capitalism in Capital. Which words most contribute to the positive and negative sentiments in Capital?

Figure 2: ‘Fall’ contributes the most to negative sentiments, although it’s my favourite season.

From this graph, a couple limitations of this approach are clear:

Sentiments are ascribed to individual words. Words like “increase” and “fall” are associated with positive and negative sentiment, respectively, but should be considered in context. The phrase “an increase in exploitation” would have a net neutral sentiment (plus one for increase, minus one for exploitation), whereas it doesn’t take a particularly discerning reader to interpret that phrase as negative. I repeated the analysis with words like “increase”, “decrease”, “fall” and “rise” excluded, and trends remained the same. More sophisticated algorithms than what I used here could address this shortcoming, but this type of classification method is fairly common.

Sentiments are ascribed using popular interpretations of the word. For example, words like “money” are associated with positive sentiments. This isn’t necessarily wrong, having money is better than having no money. But one of the key conclusions in Capital is that money inevitably arises from the circulation of commodities (a concept with negative sentiments in Capital). When Marx writes “circulation sweats money from every pore”, money isn’t being used positively; it’s a gross by-product. If we were ascribing sentiment to the word “money” in the way it is used in Capital, a neutral or negative sentiment might be closer to the “intended” sentiment of the text.

Perhaps the clearest example of differences between popular sentiment and Marxist sentiment is the word “capitalist”, the third highest contributor to positive sentiment in Capital. Let’s look at sentiments associated with similar words…

| word | sentiment |

|---|---|

| capitalist | 1 |

| communist | -1 |

| socialist | -1 |

Like with any crowd-sourced data sets, existing social biases are propagated in sentiment lexicons like the one used here. (A finding probably all too familiar to those who’ve run into issues with automated content moderation on social media sites.)

Let’s keep these limitations in mind as we test our original hypothesis: do the sentiments in Capital match a journey through Hell?

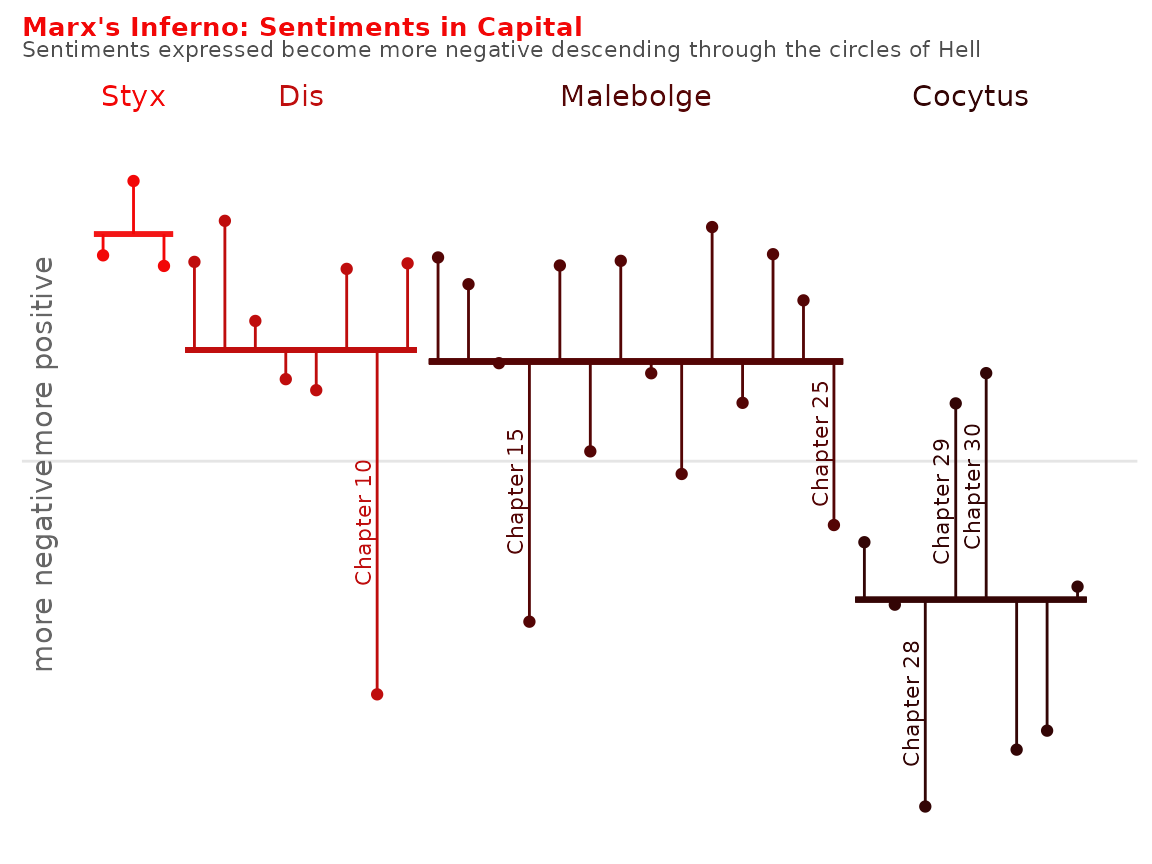

Change in Sentiment During the Descent Through Hell

In Styx, we encounter sins of incontinence, and Marx presents value theory, exchange and money. This Hell is associated with the most positive sentiments. From there, we decline in positivity into Dis and Malebolge. These circles of Hell are marked in particular by the very negative chapters 10, 15 and 25 — the “historical” chapters that describe in detail the terrible living and working conditions of British workers in the 19th century and the legal battles for labour rights. We then encounter a massive drop in positivity as we descend into the ninth circle of Hell and study the treachery of primitive accumulation. This relationship is statistically significant, for those who care about those sorts of things (p = 0.0002).

Figure 3: Chapter 10 made me feel absolutely miserable. It’s nice when data validates my emotions.

Change in Sentiments by Hell

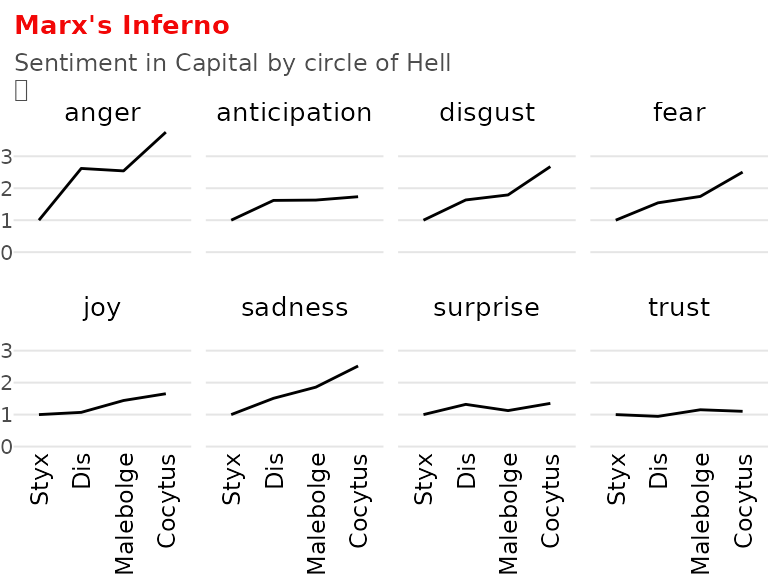

In addition to positive/negative, the NRC sentiment lexicon also associates words with one or more of eight emotions: anger, anticipation, disgust, fear, joy, sadness, surprise, trust. In the Marx’s Inferno framework, we might expect increasing anger, disgust and fear as we descend through Hell. Based on the unique characteristics of each hell, we might also expect higher surprise and a loss of trust during the last two circles, which deal with fraud and betrayal.

Figure 4: Change in sentiment across Hell for all 8 sentiments in the NRC data set (excluding positive/negative).

Breaking down the words in Capital into these eight emotional categories, we see a very strong increase in the negative emotions anger, disgust, fear and sadness (275%, 170%, 150%, 152% increase in the final circle of Hell relative to the initial circles of Hell). The uptick in joy is intriguing, but the effect size is not nearly as large as for the other emotions (65% higher in Cocytus relative to Styx). Overall, these trends are consistent with what we saw above in terms of declining positivity over the course of Capital.

The emotions surprise and trust remain flat throughout Capital, counter to my hypothesis that chapters associated with fraud and betrayal might be associated with shock and loss of faith. While this finding doesn’t necessarily provide additional support to the arguments presented in Marx’s Inferno, perhaps it was too much to demand this level of emotional granularity in the text. After all, capital’s betrayal of workers was not a particularly radical or unexpected claim to make even in 1867.

Conclusions

Over the course of Capital, the sentiments expressed in the text become increasingly negative, consistent with Dante’s journey through the circles of Hell. Similarly, anger, disgust, fear and sadness monotonically increased in intensity over the course of the book. While the approach here is fairly simple and is based on popular sentiments associated with words rather than context-specific sentiments, these findings lend support to the arguments presented in Marx’s Inferno.

While putting together this analysis, I grew a little disillusioned with available sentiment lexicon tools (see above: Malebolge, capitalism promises good and delivers evil). Tools like these facilitate extracting information from news article, tweets, or even classic Marxist-Leninist texts, but reproduce existing societal biases and hard-code in capitalist values. Presumably a sentiment lexicon crowd-sourced from socialists would associate positive sentiments with “communist” and “socialist”. How would words like “money” or “commodity” be coded? Creating a new sentiment lexicon could provide insight into how the community uses terms from the Marxist lexicon, but could also reduce bias in sentiment analysis in other applications of data science to socialist topics.

Like Dante’s Virgil, Marx tells his charges to disregard social Hell’s command — “Abandon ever hope, you who enter” — ordering them instead to “abandon every suspicion.” And, like the pilgrim in Dante’s poem, the socialists who accept Marx’s guidance are supposed to be so transformed by their journey that they will be able to withstand the purgatory through which the revolution was currently (and recurrently) travelling.

- Roberts, 2017

[My Guide] first, I second, still ascending held

Our way until the fair celestial train

Was through an opening round to me revealed:

And, issuing thence, we saw the stars again.

- Dante’s Inferno, 14th century